Marcus Harvey: History Painter, Mischief Maker & Trader in Symbols of Cultural Consciousness.

The Island (2016) Marcus Harvey

Looking at Marcus Harvey’s The Island (2017)… What to do? Laugh? Is it Casper David Friedrich’s biscuit? Art Informel oven mitt? The Great British… Sclerotic Edifice of Floating Fortress Britannia? Or weep… Babel maybe? Or something much closer to home? Doomed rock tower destined for self-destruction or simply a slow but inevitable crumbling?

Of course, Marcus Harvey isn’t going to be tied down as to any fixed meaning. When asked about his work in 2016 the artist stated that his output consists of, ‘a portrait of my own culture – proud and heroic, and also queasily guilty’. That was quoted just before Brexit. Now, in the aftermath of Great Britain cutting itself off from continental Europe, the ominous clouds of global financial instability gather overhead. With the murky isolationist depths of Farage, Trump, Le Pen and Putin growing ever bleaker, colder and blacker, Harvey’s The Island (2017) could be read as a representation of liberalism’s existential despair. An abject rocky vertical remnant: all that’s left after enlightenment values have been shuffled off the world stage. Though the blind spots of universal liberalism were always its problem.

The materials that gave rise to this 2D image are not the stuff of highfalutin, mannered creation. The somewhat degraded ink jet print of sea and sky are paired with a slabbed, hamfistedly layered pat of crank clay that’s been mercilessly prodded with a square stick. Through an unexpected, some might say idiosyncratic adoption of diverse materials Harvey surprises, confounds, broadens our expectations of and relations to the world around us. Demanding we be attentive, open to sensibilities that unconsciously passed us by or were previously willfully ignored. Not for the first time the materials comprising an artwork problematise any first impression on viewing it.

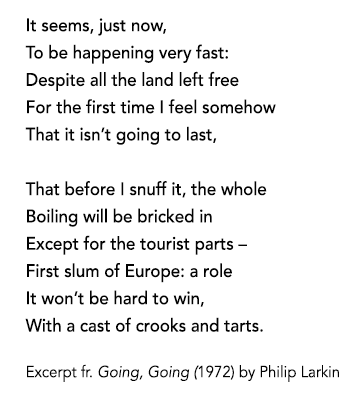

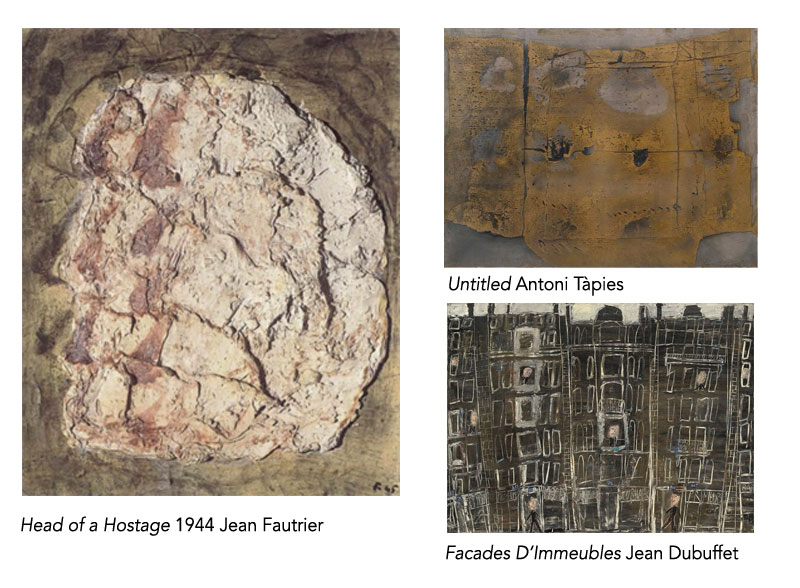

Art Informel? Okay, not abstract as such but with The Island (2017) Harvey’s aesthetic owes something surely to the likes of Jean Fautrier? Or Dubuffet’s Art Brut? Or the ravaged beauty of, say, Antoni Tàpies’ wrought surfaces. And there’s a more recent art contemporary who shares Harvey’s penchant for searching for, finding forms that aren’t simply a re-making of what’s already imagined, who kicks – chops, slashes and gouges – against any a priori mode of creation. Paul McCarthy in his Pirate Heads (2003 – 2005) is arguably seeking to surprise himself in ways not unlike Harvey’s approach: ideas and materials come alive in the process of making. This engagement with materials is not just a ‘working out’, a manifestation of the artist’s conceptual imaginary. A form has emerged from the very act of making, the premeditated gives way to a ‘coming into being’ of some thing that thrills, disturbs, confronts its maker as much as it might the viewer. It’s a modus operandi that also chimes with Philip Guston’s late painting. When Guston forwent abstraction and returned to figuration he still relished his material – the muck and whirl of it, the joy of dragging coloured mud across a surface – as an integral spur to invent the unexpected even as recognisable motifs reoccurred. Another thing that Harvey shares with the late Guston: in the midst of infectious energy and wit there emerges more than a whiff of comic bathos.

Mercilessly prodded with a stick: is that how the Brexiteers felt? Is that why they chose to ignore the blooming obvious? That the UK’s problems were and are predominantly nothing to do with Europe, they are homegrown. Policies bent on austerity, the creeping privatisation of the NHS, housing supply and costs out-of-control, income polarization, ghetto demographics… These are all issues that successive British Governments could have, should have addressed without resort to finger pointing across the channel.

A rearguard and shabby, dilapidated, necropoliptic, isolated mass: or an Ark? If so, who sails there? What’s the make-up of its voyagers? Or is that cargo: dumb freightage given one binary chance to voice a multitude of concerns? And it turns out the fifty-two percent who thought they knew where they were bound are now stuck mid-ocean in a ‘vessel’ presenting more like a warship. Mean looking windows resembling gun holes, a towering broadside to all who look towards the UK. It’s not a ‘face’ that beams friendship, rather The Island stands alone as a brittle form more bent on defining itself by identifying enemies, outside and in.

The Island as a sublime, awe inspiring biscuit dunked in a sea of troubles? No, forget Bake Off… this is The Great British Fuck Off!

Adrian Burnham